Selling Out

For the rest of the May 2009 issue of CRM magazine, please click here.

Founded in the 19th century, FAO Schwarz has seen its share of economic turmoil. Not until the start of the 21st century, however, did the toy-store pioneer feel the pain of its ultra-competitive, highly commoditized industry. Having undergone two bankruptcies in the past decade, it’s a wonder FAO Schwarz has managed to emerge again—hey, third time’s the charm—only to face what many are calling the worst economic crisis in modern American history.

When Lee Bissonnette, FAO Schwarz’s senior vice president of direct-to-consumer, signed on for the job last May, he had set what he later admitted to be rather optimistic goals: increase sales by 30 to 40 percent; double the customer list size; and increase conversion by 10 percent. His outlook for this year was far more conservative: increase site traffic by 10 to 20 percent; maintain flat sales; increase units per transaction by 20 to 30 percent. At this point in the game, Bissonnette told the audience at this year’s eTail West conference in Phoenix, retailers have to be realistic.

In February, the U.S. Commerce Department reported a surprising turnaround in January sales—a 1 percent increase, despite predictions that the industry would continue its six-month-long decline. Nevertheless, published reports still pegged overall retail sales down 9.7 percent year-over-year in January 2009—and the industry shed another 45,000 retail jobs that month alone.

Household names are disappearing: Circuit City, Linens ’n Things, The Sharper Image, and CompUSA—to name just a few—closed their brick-and-mortar locations or moved online, and Virgin Megastores will be closing all its North American locations by summer. Analysts can’t help but label the trend one of “retail Darwinism.” Only the strong—those that have the most cash, or those able to provide unparalleled customer experiences—will survive. Unfortunately, the shakeout has only just begun. “The cost of mediocrity now is higher than it used to be,” says Michael Whitehouse, senior marketing analyst at customer satisfaction solution provider iPerceptions.

No Money

Consumer actions provide a clear indication of their spending habits and concerns about the unstable economy. Market research firm Leo J. Shapiro and Associates conducts telephone surveys of 450 United States households monthly. According to the survey conducted in the first 10 days of February, 63 percent of respondents indicate that they’ve “cut back on their standard of living,” up from 51 percent in January. Moreover, 59 percent report that a member of their household will suffer a job layoff or an earnings interruption in upcoming months; and 38 percent of households report a decrease in their year-to-year income, the highest the firm has seen in at least a decade. All last year, the ratio was in favor of income increases: In December, increase to decrease was 35 to 32; and just six months prior in July, it was 44 to 24.

“Spending,” says George Rosenbaum, cofounder of Leo J. Shapiro and Associates, “is very much correlated with how much income people have and—independent of income—how scared they are and how cautious they are about holding onto their money.” According to the study, savings rates in January and February were 43 and 42 percent, respectively, compared to just 37 percent in October. “You not only have declining income, which is a pragmatic factor in retail spending,” Rosenbaum says. “But you also have a concern about holding onto money and savings.”

If they haven’t personally endured the financial devastation, consumers are reluctant to spend; in fact, many feel guilty if they do. “They’re being told not to buy,” said Carl Prindle, chief executive officer of Furniture.com, at eTail West. “They need some excuse to push them…to do something they’re being told not to do.” But for now, Rosenbaum’s research indicates that customers are bracing for the worst—70 percent of the people believe the recession is going to last three or more years.

On Sale Now!

For retailers, price cutting is just the point of entry. “Thirty percent off is the new list price,” says David Fry, president of Fry, his eponymous e-commerce solutions firm. Consumers are expecting more, but paying less. In this market, that’s the only way to play. “People are being trained right now to expect these promotions,” he adds. “And retailers right now don’t have the confidence to hold off on promotions.”

In an electronic poll of the audience at February’s eTail West conference—which gathered just under 850 vendors and retailers, down from 1,200 the previous year—83 percent of respondents said they had increased online advertising and promotions to stimulate sales during the holiday season.

Not all retailers are giving in. Pottery Barn, for one, is standing firm, refusing to slash prices. West Elm, however—a lower-end competitor—is “cutting deep and cutting early, because that’s what helps the bottom line,” says Scott Couvillon, president of direct marketing agency Dukky, of the daily emails he receives from the furniture retailer. The path to take depends largely on how much cash a company has, but it’s difficult to determine which will prove the winning choice. Chicago-based retailer Wrigleyville Sports, for example, saw a 16 percent increase in sales this past holiday season, but only a 5 percent increase in revenue. (For more on Wrigleyville, see this month’s Real ROI.)

“Most of our customers did sell more than [during] the previous holiday,” David Fry says. “But almost every customer reported lower cost margins…. The real issue is value to consumers—as it’s always been—but our filters are tighter.” Perks, such as free shipping or two-for-one, are drawing consumers like moths to a flame, but for how long?

Online versus Offline

According to a January 2009 report by brand consultancy Interbrand Design Forum, department stores have long been on the path to extinction. Traditional models of retail success were based on one criterion: location. Suffice to say, location has its price. Real estate costs are hampering long-established brick-and-mortars—such as the 850-plus locations of department-store giant Macy’s—in this increasingly digital environment.

Starting online is not as easy as setting up a Web page and calling it a store. The effort requires fundamental changes in business model. While it would be difficult for Macy’s to exist solely online, it would be easier, in Couvillon’s opinion, for online retailers to move into the physical world. “From a philosophical standpoint,” Couvillon says, “[online retailers] understand that overhead doesn’t have to equal sales.”

Fry says a retailer’s investment in an e-commerce system today is probably comparable to what it was in years past, but the functionalities have improved and expanded significantly. “When retailers started sites 10 years ago,” he says, “it was all fanciful.” Sites continue to raise the bar, with the ultimate intent of replicating—and sometimes surpassing—the in-store experience. Robust capabilities include search, sorting, navigation, dynamic imaging, video footage, product ratings and reviews, even product-recommendation engines—all geared to provide consumers with a highly relevant experience, while motivating them to spend more.

Aside from operational benefits, companies have to be online simply because that’s where the consumer is. “It’s a lot harder to find the [retailers] who shouldn’t be online than the ones who should,” Fry says. But the real issue here isn’t “online versus brick-and-mortar.” Consumers want not just a multichannel experience, but a cross-channel one. “Your customer thinks of you as one business, so you should think of yourself as one business,” Fry asserts. “A good retailer wants to be involved in as many conversations as possible.” (For more on multichannel operations, see “In More Ways Than One.”)

Retailers reluctant to invest in their online storefronts claim that, because only a small percentage of sales come from the online channel, the returns are not worth the cost—a rationale that Fry characterizes as flawed. Some of the strongest online retailers only see 10 percent of their revenue online, he says, but as much as 70 percent of their overall transactions are influenced by their Web sites.

Just as costs are lower for the online retailer, the online shopper expects to find the lowest-priced items. If prices are the same as they are online, Couvillon says, consumers might prefer the offline store for the tactile experience. Competitive pricing, regardless of channel, is taking away online retailers’ foremost advantage. On top of that, brick-and-mortars are attempting to propagate the promises of the online world: For example, Clearview Mall, located in the New Orleans suburbs, will be focusing its new marketing strategy on “convenience and value at the mall you love,” says Joy Patin, the shopping center’s head of marketing.

The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) judges customer satisfaction in the e-commerce sector based on four major attributes: content; merchandise; price; and functionality. Results from last year’s fourth-quarter report indicated that, for the first time, price had a significant impact on customer satisfaction.

“[It will be] interesting to see if, as the economy stabilizes and…starts to improve, does it shift back?” asks Larry Freed, president and chief executive officer of ForeSee Results. “Or do Wal-Mart and Target take advantage and keep those consumers for a long period of time?”

Consumers are influenced by multiple channels, and expect to be able to transact anywhere they want. And even successful multichannel retailers are realizing that managing cross-channel behavior is increasingly complex. (See “Shopping On the Go,” in this month's Insight, for a look at mobile shopping.)

“I have, unfortunately, worked with companies that say, ‘I don’t want my call center to direct someone to buy online because I won’t get credit for that sale,’” Fry says. “And when you have an organization set up that way, it’s not going to give the best experience for the customer.”

Fry says that, in retrospect, the bankruptcy filing by Circuit City—a client of his—isn’t all that surprising. Despite his own personal and professional investment in Circuit City, he says he recognized the clear flaws in its operations. “I’d go into the store and there’d be one sales clerk working a checkout line of seven people, answering the phones, dealing with returns,” he recalls. “She looked like she was going to kill herself.”

At Circuit City’s upper-management level, he says, conversations around strategy, such as the rebate process, ran like the typical retailer’s trap: Customers had to fill in a form, mail it in, and wait between four and six weeks for the return. When Fry suggested making rebates available online to simplify the process, the company declined, stating that the customer’s negligence was its gain.

At Your Service

Manipulating price will increase traffic into your stores and push products off your shelves, but its ephemeral impact is akin to “shock therapy,” iPerceptions’ Whitehouse points out. Now, more than ever, a company needs to be innovative, and, more important, needs to restore consumers’ confidence—confidence that they’re buying what they want, what they need, at the price they can afford. (See sidebar, “Know More, Shop More,” below.) Consumers today are riddled with cynicism, and rightly so. The only way to win them back, Whitehouse says, requires retailers to diverge from the monochromatic shopping experience they could get anywhere else.

While dynamic imaging and other online bells and whistles are lovely, experts agree that only a sustained commitment to the customer-centric experience will sustain the retail industry. Quality service will be the ultimate differentiator between the winners and the losers.

According to the ACSI, both retail and e-commerce have managed to maintain relatively high levels of customer satisfaction. Retail actually improved from 74.2 on a 100-point scale in 2007 to 75.2 in 2008. Meanwhile, online retail dropped from 83 to 82—primarily due to Amazon.com’s drop from 88 to 86, and online auction site eBay’s fall from 81 to 78. Even so, says Claes Fornell, head of the ACSI, “these are generally very, very high scores.”

Service, asserts Bill Knight, president of The Wine House, is “what’s going to differentiate me from all the big boys trying to take my business away.” At the time of reporting, Knight was planning to host wine-tasting dinners for a well-segmented group of customers. The planned event was to include eight to 12 different wines in addition to dinner, for approximately $200 an individual. The goal, he says, is to “provide a ‘wow’ experience to do something special and keep them affiliated.”

When times are tight, the easiest things to neglect are basic investments that inevitably impact the shopping experience. “You can’t shave off parts of your body to become a great athlete,” Fry says. During the last holiday season, a large number of retailers couldn’t handle the influx of online customers, causing site-overload problems, and impeding sales.

According to a New York Times blogpost the day after the presidential inauguration, the influx of consumers rushing to clothing retailer J.Crew’s Web site managed to crash the page featuring the gloves the First Lady wore, and hours later, the site’s entire women’s section. The site’s apology read, “Sorry, we’re experiencing some technical difficulties right now (even the best sites aren’t perfect). Check back with us in a little while.”

The Bright Side

After reveling in years of what Dukky’s Couvillon refers to as “economical drunkenness,” retailers are finally sobering up. As long as money was coming in, retailers became “rich and lazy,” he says, and consumers could afford not to care. What this recession may achieve is, ironically, something that the industry desperately needs: some rightsizing.

The term “rightsizing,” Couvillon notes, isn’t in the consumer vernacular. Theorists argue that the industry is undergoing a correction—retailers will begin charging a fair value and consumers will purchase with discretion. “I don’t think the average consumer is angry about it, but I think they definitely get it,” Couvillon says. “You’re going to see a return to marketers being extraordinarily smart about their investments, getting away from nonmeasurable activity, and increasing their accountability.” (See the sidebar, “Measure for Measure,” below.)

In the same respect, customers will become smarter and more responsible about their consumption. “Maybe I’m an optimist,” Couvillon says. “We’re going to have a smaller retail economy, but a smarter retail economy…and the [survivors] will have great relationships.”

.

SIDEBAR: Measure for Measure

Measurability is critical in a numbers-driven economy, especially when retailers have the added burden of managing inventory. “You can’t manage what you can’t measure,” says ForeSee Results’ Larry Freed. “Measurements must be accurate, precise, reliable.” Otherwise, it’s garbage in, garbage out. Some companies have begun cutting inventory entirely, preferring to go out-of-stock than order too much. Promotions may drop off, says David Fry, of solutions provider Fry, but retailers are not running to restock—a short-term strategy, he says. “It’s going to have a negative impact on consumers.”

Retailer: Cabela’s

Vendor: SAS

Problem: Understanding how to maximize advertising and marketing dollars.

Solution: “We’ve been able to better understand what our email campaigns do, what our paid search, [search engine optimization], and catalogue returns provide us, and how our retail-store locations are doing,” says Corey Bergstrom, director of marketing research and analysis for Cabela’s. By monitoring the performance of every dollar, he says, the company is able to make shifts toward channels that provide the highest returns.

Retailer: The Wine House

Vendor: SAS

Problem: Cut costs and move old inventory.

Solution: The Wine House was able to identify and sell $400,000 worth of inventory—1,000 cases of wine—that had not moved in more than a year, says its president, Bill Knight. “Sometimes our inventory ages well,” he says, but it was extremely fortuitous that the company was able to bring in that extra cash flow just a month before the economic meltdown in September. Thinking back, Knight says that, had he discovered the old inventory any later, it really wouldn’t have moved during the holidays. What the additional revenue provided instead was the ability to buy goods during the holidays and afford him the flexibility to engage in promotions. “We were actually generating gross profit,” he says.

Retailer: Elie Tahari

Vendor: IBM

Problem: Improve customer service and cut costs.

Solution: In the words of Heidi Klum, “In fashion, one day you’re in, the next day you’re out.” For that reason, explains Nihad Aytaman, director of business applications at Elie Tahari, inventory is manufactured at the last moment. As a result, 80 to 85 percent of goods require air-based shipping—a method, Aytaman notes, three times more expensive than shipping by boat. With IBM’s business intelligence (BI) technology, the company was able to integrate the information from the production cycle to sales, its factory schedule, and customer commitments to streamline its shipping processes and reduce to 50 percent the share of goods shipped by air. Moreover, Aytaman recalls a conversation with one retail manager who said that, as soon as the BI system went live, she completely changed her entire buying pattern after discovering that the sizes she was purchasing were the reason for weak sales. “It’s obviously about getting the right product on the floor,” Aytaman says.

In addition, streamlining the company’s entire inventory made it significantly easier to access. Across its seven retail stores and 12 outlet stores, if an item is not available in a particular location, associates were finally able to reduce what used to be a five-to-10-minute process of searching the database down to just 10 to 15 seconds, he says.

.

SIDEBAR: Know More, Shop More

“Technology,” according to Scott Couvillon, president of direct marketing agency Dukky, “is the reason consumers are in control right now.” Just a few years ago, “research” rarely went beyond asking a friend or watching the news. Now, as a result of an economy that’s forcing them to fine-tune their selection process and an industry that’s pregnant with choices, consumers are apt to seek advice—even if it’s from a complete stranger. For a marketer, it’s disheartening to witness a random blog post carry more weight than a million dollar commercial.

According to a late 2008 study conducted by JupiterResearch, now a Forrester Research company, consumers today are more open to being influenced on decisions surrounding what item to purchase, when to buy, and where to go—a 24 percent, 29 percent, and 20 percent increase, respectively, over responses from 2004. Retailers have the opportunity to influence consumer purchases by optimizing transparency and accessibility to information.

One leading source of information is ratings and reviews written by fellow shoppers, or “a person like me.” (For more on user-generated content, see “Power to the People,” December 2007; for more on the importance of the “trusted source like me,” consult Paul Greenberg’s July 2008 Connect column, “A Company Like Me.”)

According to Sam Decker, chief marketing officer of social commerce technology provider Bazaarvoice, 97 percent of customers trust product reviews. The majority of the top 100 online retailers have product review capabilities on their Web sites. While many consumers would claim that this feature is prevalent, there are many companies—particularly small businesses—that could really use the influence of what consumers perceive to be unbiased promotion.

The benefit of reviews has also motivated merchants to game the system, as was the case with electronics manufacturer Belkin in January 2009. A Belkin employee was exposed for paying 65 cents each for positive reviews of Belkin products, coupled with a ranking of negative reviews as “not helpful.” Although 65 cents seems like a trivial amount, the problem with the situation is a question of authenticity. Social commerce platforms like Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews provide both technology to protect against fraud, in addition to human moderation.

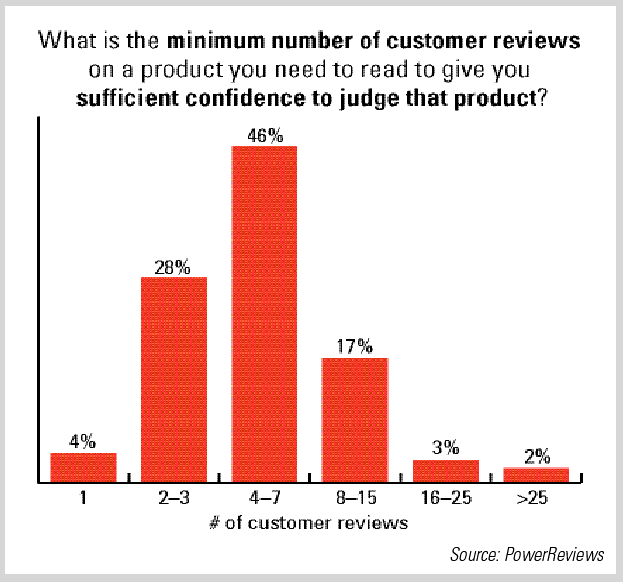

To prevent fraudulent reviews, and mitigate the risk of being viewed as inauthentic, some companies are contemplating limiting reviews to only those who have purchased an item directly from the site. Bazaarvoice offers this capability but concedes that it’s “a little bit of overengineering,” Decker says. The company’s own customers have reported back saying that they don’t want to discredit a review just because it came from a different source (e.g., someone who purchases from Borders but comments on Amazon.com). PowerReviews offers a “verified buyer” identification that serves to add credibility to the review, but does not restrict the “unverified” from posting a review. Especially in a cross-channel retail environment, Decker says, “why would you exclude the participation of the rest of your customers?” (See bar graph, below.)

“That’s the rule of Web 2.0,” says Darby Williams, vice president of product management at PowerReviews. “You never want to prevent someone from letting their voice be heard.” According to Bazaarvoice, 90 percent of reviews are intended to help others, but for the remaining 10 percent, the crowd won’t be so easily duped.

“It’s a smart crowd,” Williams says. They trust critical reviews more than they do five stars and infinite praise. “They’re the biggest protection [against fraud] out there,” he says.

.

SIDEBAR: Buying by the Numbers

More than 50,000 retail-consumer respondents participated in an iPerceptions survey last December. Here are some of the relevant results:

Why Consumers Go on Company Web Sites

34% to research/learn

25% make a purchase

15% promotional clipping

10% look for company information

8% browse products

8% other

Why Consumers Who Want to Buy, Don’t

38% not able to find what they were looking for (due to site navigation, inability to match content seen offline/online, site search tools, ability to deliver products that match up with user needs)

17% product availability

15% usability of site

15% pricing

15% others (long tail)

.

SIDEBAR: Technology Can Help Seal the Deal

Software users can—and should—lean on their vendors for what they’re worth (and even to negotiate for better subscription rates). Jamey Maki, director of online marketing and analytics at golf equipment retailer Golfsmith, told the audience at eTail that he demands that vendors plot out how they can make him profitable on a simple Excel sheet. “Until they do,” he said, “I don’t even talk to them.”

Vendors, too, are aware of their roles in helping their customers optimize the value of technology. Price management solution provider Vendavo announced this past February its Strategic Customer Organization (SCO) to help nurture its customer relationships and deliver actionable business strategies. “We saw an opportunity to help our customers achieve even more value by advising them on their long-term profitability goals,” explains Jennifer Maul, Vendavo’s chief customer officer. While the company itself doesn’t focus on retail specifically, Maul emphasizes that this objective is applicable to all software vendors. “Business strategies must complement [technology] deployments in order to maximize the value,” she says.

Assistant Editor Jessica Tsai can be reached at jtsai@destinationCRM.com.

Every month, CRM magazine covers the customer relationship management industry and beyond. To subscribe, please visit http://www.destinationcrm.com/subscribe/.